Towards the end of Issui Ogawa’s 2003 The Next Continent we learn something about Tae Toenji’s true motives in establishing a moon base. I briefly noted this revelation in my recent moon base essay and commented that seeking therapy would have been far healthier and more cost-effective than the course of action Tae actually embraced. I then realized that this was an idea on which I wanted to follow up….

People will do ambitious but wildly irrational things (set up a moon base, try to conquer the world, etc.) rather than admit they have emotional problems they just cannot face without help. We see this in real life and we see it various science fiction and fantasy works. Here are five examples.

Detective Comics #33, by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger (1939)

Having resolved to rule the world with the amassed scientific genius of the so-called Scarlet Horde, Napoleon-wannabe Krueger begins with a fatal misstep. Of all the cities he could select as a base of operations, he chooses one under the protection of the costumed vigilante, the Bat-Man. Success is therefore not only not guaranteed, it is assuredly impossible.

Although the cowled figure known to Gotham City’s underworld as the Bat-Man had appeared in Detective Comics #27, it was not until issue 33 that readers learned what motivated seemingly indolent playboy Bruce Wayne to spend his nights crime-punching in a bat-themed costume. The answer is anger and grief at his parents’ violent murders. That his preferred methods don’t seem to be making any headway against Gotham’s crime problems, or might even be making them worse, does not seem to occur to Wayne.

Wayne does have a legitimate excuse for eschewing conventional therapy, although he may not have been aware of it when he resolved to become a bat. For reasons that escape me, virtually every named therapist and mental health professional in the DC comics universe ultimately turns out to be deranged, criminally inclined, or both. At least Marvel superheroes can turn to Doc Samson.

Space Viking by H. Beam Piper (1962)

The wedding of Lady Elaine and Lucas, Lord Trask would have been picture perfect. Too bad that rejected suitor Lord Andray Dunnan interrupts things with an assassination attempt. Trask survives but Lady Elaine is killed. Dunnan flees in a stolen starship into the depths of the old Federation (which has left behind a slew of settled but poorly defended planets).

Trask heals from his injuries and vows revenge. He recruits a crew for his own well-armed starship and sets out to track down Dunnan. Dunnan has gone a-viking, holding planets to ransom and looting the defenseless. Trask engages in a bit of piracy himself. He must, after all, pay his crew and stock his starship. Tens or hundreds of millions die.

Trask might well have benefited from the services of a trained mental health professional. It’s certain that the multiple continents-worth of victims he hellbombed would have been better off had he made that choice.

Dragon Sword and Wind Child by Noriko Ogiwara, translated by Cathy Hirano (1993)

Orphan Saya is wooed by divine Prince Tsukishiro. Although this is the first time in her life Saya has encountered Tsukishiro, it is not their first meeting: Saya is the reincarnation of the Water Maiden Sayura. The prince has wooed many of Saya’s previous incarnations. The relationships always end badly for Saya. Or so it seems.

The conflict driving the plot: the wife of the God of Light, the Goddess of Darkness, suffered grave injury when she gave birth to the God of Fire. The God of Light killed the Fire God, sealed his wife into the Underworld, and launched a bold scheme which will lead to the death of all mortals.

I am not going out on limb here when I suggest that consulting a trained therapist would have been a far superior choice than the ones the God of Light actually made. The Goddess of Light, for her part, could have used a talented divorce lawyer, another profession in woeful short supply in fantasy.

The Quantrill Trilogy by Dean Ing (1981 – 1985)

A fortuitously timed Boy Scout outing saved Ted Quantrill from being one of the hundred million American casualties of World War Four. A talent for killing helped the boy, soon a man, survive the horrors of war and the excesses of the peace that followed. How long Ted will survive confronting danger after danger at the behest of his employers is an interesting question. The truncated life spans of his fellow operatives suggest that his will be a brief but interesting life.

Unlike most of the examples on this list, the issue here isn’t that there are no therapists (this is the US of the future, so they probably exist), or that Ted shuns therapy (it’s never offered). The issue is he is far too useful to the American government as a trauma-numbed survivor for anyone to consider allowing him access to such services.

The trilogy (Systemic Shock, Wild Country, and Single Combat) does show Ted inching toward a healthier life, development that will in no way be due to his bosses.

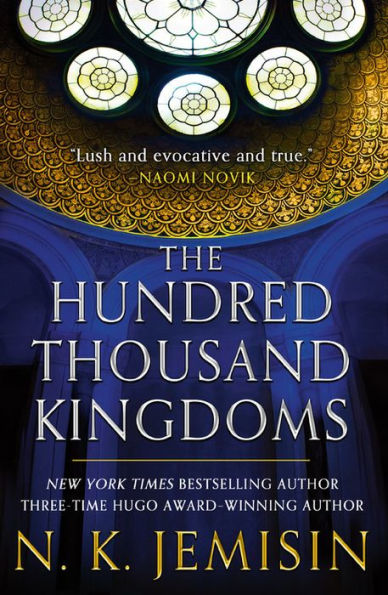

The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin (2010)

Summoned from her distant satrapy to the Arameri world empire’s capital of Sky, Yeine learns that she is now one of her grandfather Dekarta’s three designated heirs. Wealth and status are hers… at a cost.

Dekarta is a high-ranked Arameri, ruling the world on behalf of the god Itempas. Being his successor is a goal worth killing for—thus the corpses of several heirs whose prudence proved insufficient to guard against their rivals’ homicidal creativity. Can Yeine prevail in this unfamiliar city? Or is she merely a walking corpse to be?

As with Dragon Sword and Wind Child, the backstory to the conflict highlights the dire shortage of therapists qualified to provide marriage counseling to quarreling gods.

***

One hopes this essay does not come off as needlessly jocular or in any way making light of the value of therapy and counseling. There are many, many reasons to consider seeking the services of appropriate mental health professionals, and all of them are valid. And of course, there are plenty of examples of fictional characters who fulfill their narrative role while also attending to their mental health. (Well, maybe not “plenty” of examples, but they exist!) That, of course, is a matter for another essay.

In the words of fanfiction author Musty181, four-time Hugo finalist, prolific book reviewer, and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll “looks like a default mii with glasses.” His work has appeared in Interzone, Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis) and the 2021 and 2022 Aurora Award finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by web person Adrienne L. Travis). His Patreon can be found here.